Celebrating 25 years of ParkPro

An interview with North America's longest-tenured employee, Harry Turgeon.

It was the first of it’s kind 25 years ago. Now it’s the best-selling snowcat in North America.

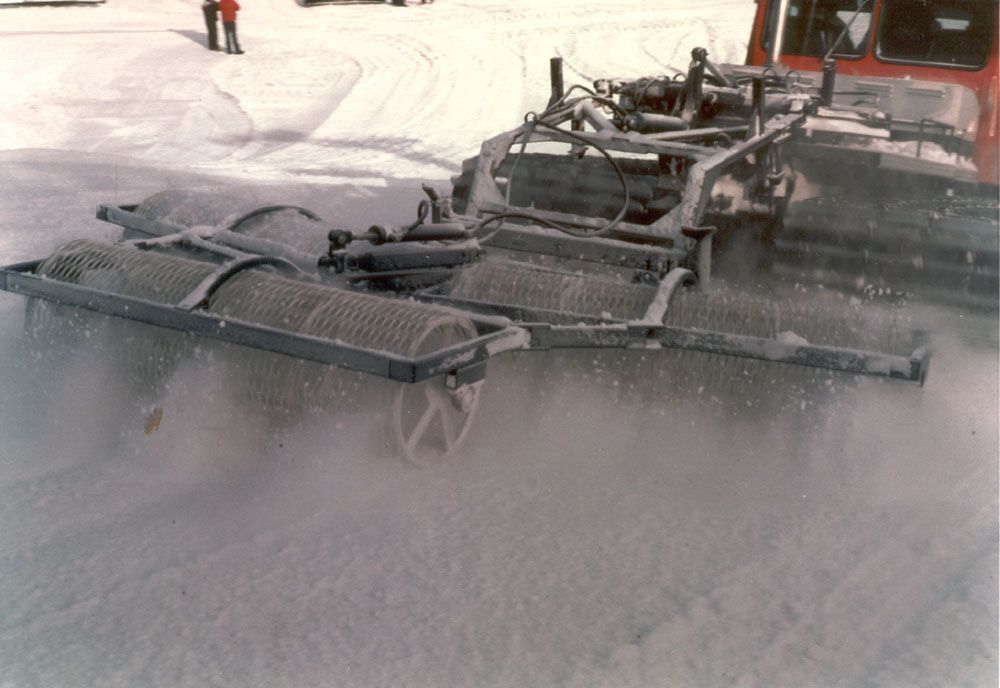

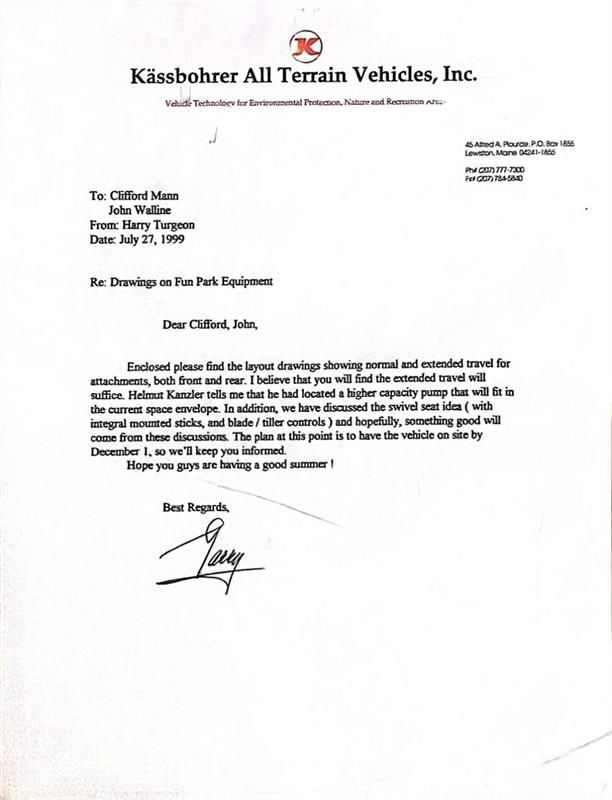

In May of 1999, a collection of industry leaders and personnel from Kässbohrer All Terrain Vehicles, Inc. met to discuss the idea of a “Terrain Park Vehicle,” a machine that allowed for increased articulation of both blade and tiller. Production ensued that Fall, and by early 2000, the very first Park Bully was on the market in North America. Now known as the ParkPro series, these incredible machines continue pushing boundaries of what can be built with a PistenBully. To celebrate this milestone, we will be sharing the stories of some of the central people who helped make the Terrain Park Vehicle possible. This is the story of Harry Turgeon, Kässbohrer All Terrain Vehicles, Inc.’s longest-tenured employee, who retires this month after 55 years with us.

Harry Turgeon has been at Kässbohrer All Terrain Vehicles, Inc. since 1969, boasting an incredible 55 years of service. He has been lucky enough to be a key player in some of snow grooming’s most remarkable equipment developments over these decades, many of which he created the original engineering drawings for.

Harry always liked art as a child. He was born and raised in Lewiston, Maine, where he loved drawing more than anything. He dreamed of being an artist – or at least being able to draw every day. That’s why, just after high school, he enrolled in a two-year program at a vocational tech school in central Maine where he learned how to do mechanical drawing.

Halfway through his second year of school, Harry started doing some part-time work for a little business called Valley Engineering. Valley Engineering was run by one of the owners of Lost Valley Ski Area, and they needed someone to record and formalize the drawings of the Powder Maker that they had recently built and patented. (A Powder Maker would attach to the back of a snow grooming machine, a very early relative of today’s tiller.)

Harry’s job was to transform the rudimentary sketches of the Powder Maker, found on napkins and loose papers, into finite, professional drawings. He did this while still in school, which he completed in December of 1969. Just before Christmas of that year, Harry joined Valley Engineering’s team of three as the fourth full-time member.

Soon, Harry went from simply transposing drawings to helping with the development of other pioneering equipment. In the early 70s, snow groomers did not have blades or tillers; the machines were essentially pulling around a piece of equipment to break up the snow. Valley Engineering saw the need for a blade to push snow with the front of the snowcat, particularly a blade with better articulation of movement. They were able to patent the very first 8-way moving blade: up, down, left, right, left-up, left-down, right-up, right-down.

From there, they began to develop a whole family of parts and implements that would improve snow grooming, including patenting a rear frame. This frame was called the “hydrosaddle” and it essentially created a fifth wheel that could be mounted on the back of a snowcat which also assisted with steering.

This type of innovation was distinctive to Valley Engineering, Harry says. What made the company stand out when they first started was how they carried their farming background into their work. Agricultural machines such as tractors tend to work like a multitool: you can add different attachments to the back to get a desired outcome. Valley Engineering had this same philosophy, which they adapted and brought to snow grooming.

The hydrosaddle frame was a hit and it continued to progress, with Valley Engineering forming partnerships with all the name-brand snow grooming companies of that era. In early 1973, one of the owners of Valley Engineering made contact with Erwin Wieland from PistenBully, a subsidiary of Kässbohrer. PistenBully machines had already been imported to the United States by that point. In fact, Harry had seen the 145 model in person when it was first introduced at a show in the US.

Several Kässbohrer employees decided to travel from Germany to the Northeast to scout out Valley Engineering. It was Harry who picked the Germans up from the airport for that first meeting. From there, the Kässbohrer team was brought to a show where they were able to view Valley Engineering equipment up close. They were impressed, and eager to use the equipment with a PistenBully.

That same year, Valley Engineering started producing equipment for Kässbohrer. Harry made his first trip to Germany in 1973, too, where he got to visit the Kässbohrer factory and view the production line in person. (This was the first of more than a dozen trips that Harry would make over his career with the company, the longest trip being nearly a month to help write an operating manual).

Though Valley Engineering was working with most of the known snow grooming companies of the time, Kässbohrer accounted for about 70% of the business. It became clear that it was in the best interest of both companies to align fully in order to progress. In 1979, Kässbohrer bought Valley Engineering, making them Kässbohrer Valley Engineering, the official distributor of PistenBully in North America. All ties were immediately severed with any other snow grooming distribution company.

Kässbohrer Valley Engineering continued to grow. They had established a strong distributor network across the country and were the clear industry leader in snow grooming. Significantly, in the mid-1980s, they developed the winch in tandem with Mammoth Mountain. The winch first appeared on the PB200DW, which was equipped with a 360-degree pivot table and boom, allowing the machine to hook up to pick points at the top of the slopes. The winch became standard for steep-pitch grooming.

The North American side of PistenBully was now more of a sales and service distributor rather than a manufacturer, with a wide and popular market. At the same time, the ski/snowboard discipline of terrain parks was growing in popularity, too. By the 90s, it became clear that park building was now an established art of its own, with a strong desire for highly specialized tools to get the job done. It wasn’t long before Harry was working on another significant innovation from North America: The Terrain Park Vehicle, which today is known as the ParkPro.

In 1999, Kässbohrer Valley Engineering, which was now Kässbohrer All Terrain Vehicles, Inc., moved from Maine to Reno. Harry moved with it for a short period of time – just three years before returning to Maine – but in that timeframe, he was able to be in close proximity to Mammoth Mountain as they helped to develop the Terrain Park Vehicle. In fact, the resulting Park Bully was one of the last engineering projects Harry worked on before switching his 30-year engineering career to work in the logistics branch instead.

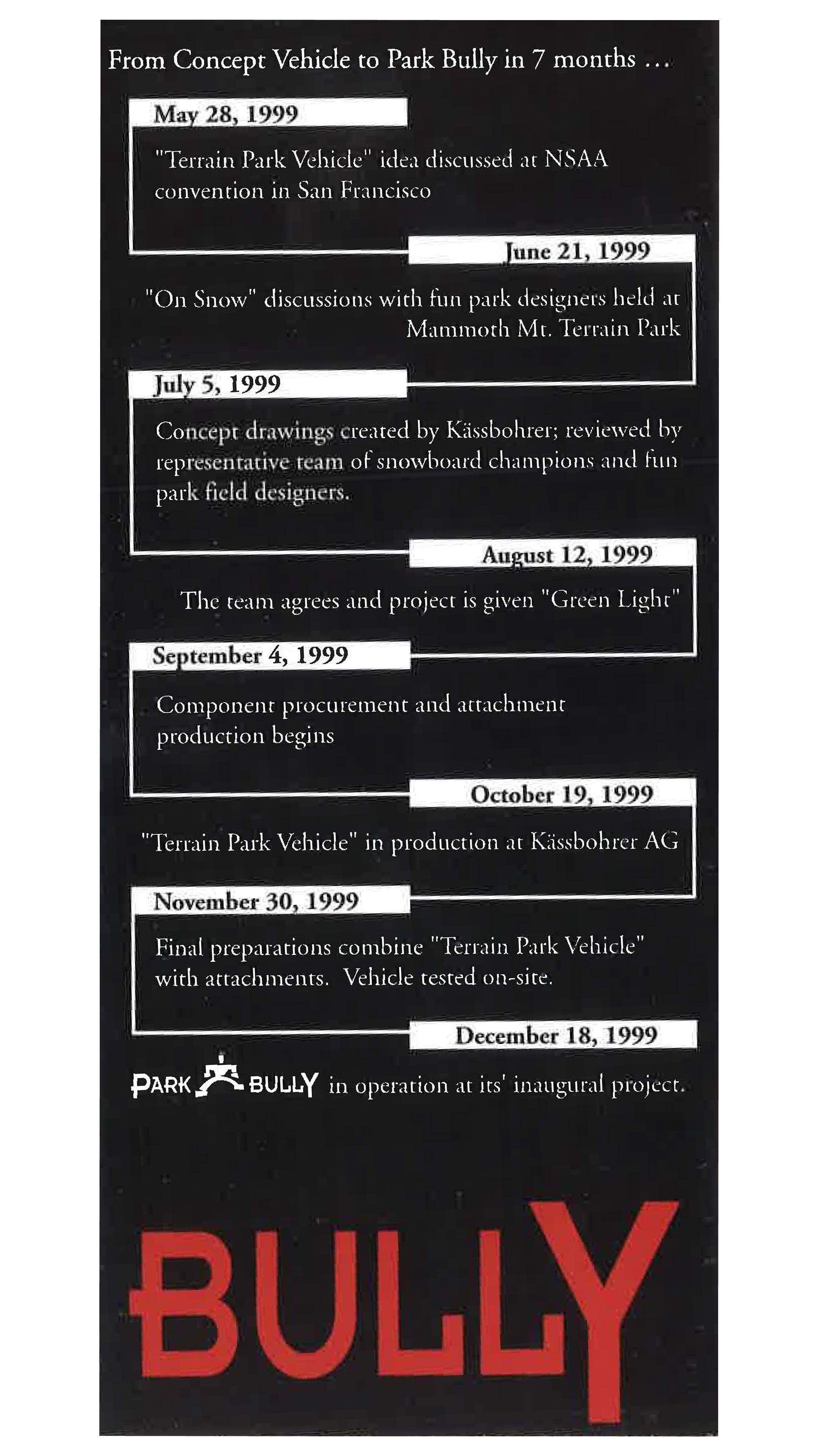

In the spring of 1999, members of Kässbohrer All Terrain Vehicles, Inc., including Harry, met with personnel from Mammoth Mountain and other industry leaders to discuss ideas for new machine implements. Terrain Parks were growing in popularity, with Mammoth at the forefront of pushing boundaries for what a jump or a feature could look like. They needed machines that could do more: A tiller that could higher. A blade that could cut below grade. The implements needed to have more articulation of movement.

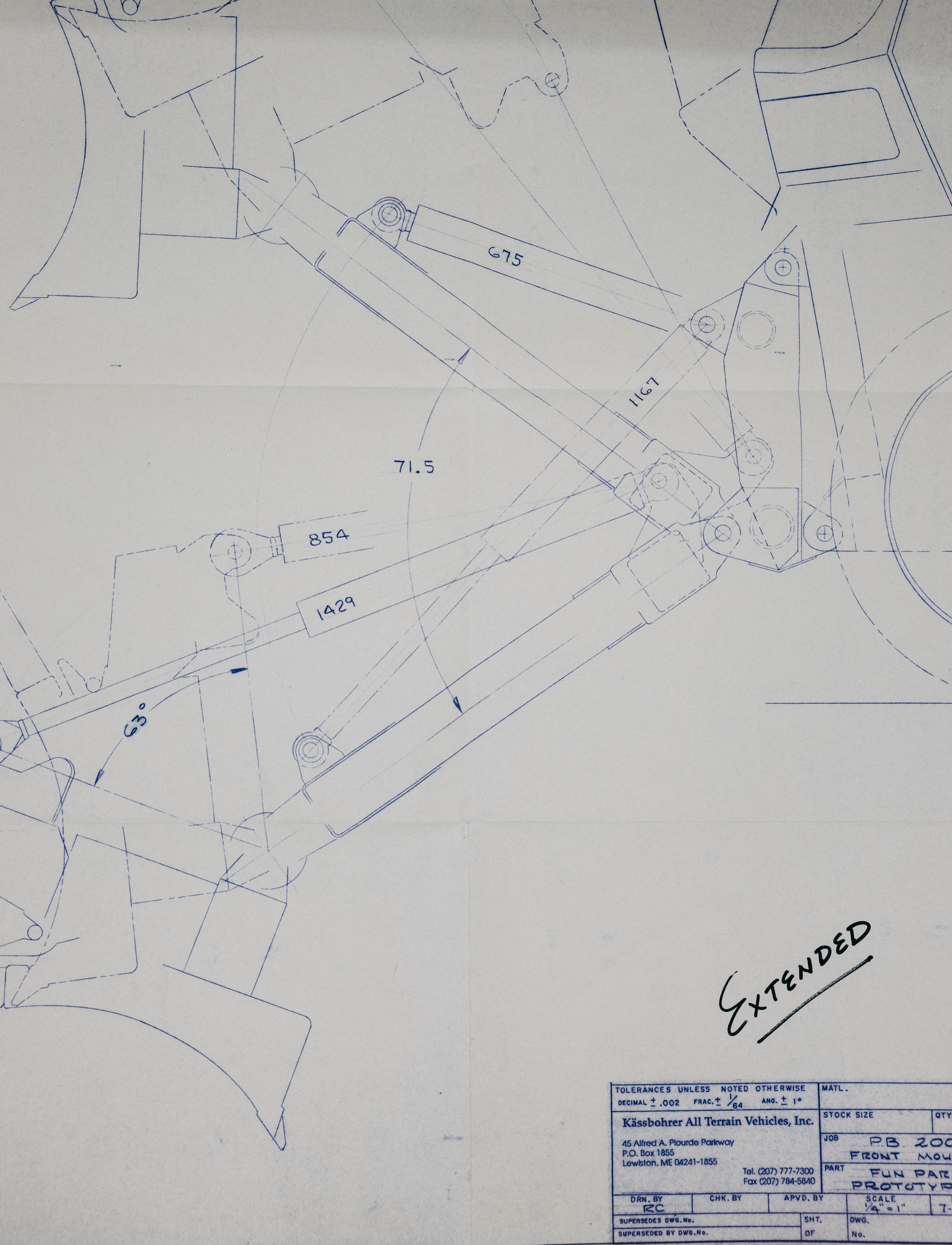

What resulted from their discussions was the idea for the very first park-specific machine, a PistenBully with a blade and tiller that could reach higher or lower than the standard blade. Harry drew up the very first concepts of the implements at the beginning of that summer. By July, the innovation team had gotten the green light, and production in Germany began in September. In December, a prototype of the very first Park Bully was unveiled. A few months later, in the year 2000, it became available for sale in the North American market.

An early 2000 flier from Kässbohrer boasted that the new machine was “perfect” for terrain park building. “Newly designed front and rear quick mounts provide the extreme range of travel required to groom terrain features. This is made possible through geometric changes and the hydraulic cylinders. These features enable the creatin of terrain contours such as spines, gaps, serpents, rails, and tabletops in a fraction of the time.... Put the finishing touch on the same wall with the multi-flex tiller.”

A letter from Harry Turgeon to Clifford Mann and John Walline at Mammoth Mountain with an update on the Terrain Park Vehicle.

Harry's original engineering drawings for the Terrain Park Vehicle blade and tiller.

One of Harry’s favorite features of the Park Bully blade came just a bit later: the forks used for moving park features around, which we now call “switchblades.” This feature was developed at Palisades Tahoe Ski Resort (which at the time was still known as Sq**w Valley), coincidentally by a vehicle mechanic who was also named Harry.

Though Harry Turgeon was an integral part of nearly every significant PistenBully development, he doesn’t like to claim full responsibility for any of these accomplishments: There were many colleagues who he shared them with over the years. “A lot of what I would take credit for was actually shared with these people, too,” he says.

Since Harry has now been with Kässbohrer for over 55 years, it was hard for him to pin down a project or innovation that he was most proud of. There’s no one experience that stands out as his favorite or his most cherished. It was all cool. It was all interesting and special. “It was fun to be on the ground floor of an industry and watch it climb,” Harry explained. “When we started, there was nothing out there like we are doing today.”

What kept Harry here for more than 5 decades was the work itself. “I found it challenging. Exciting,” he explained. “I know some people will say that they dread going to work, and I just thank my lucky stars that I never had that. I’ve always enjoyed what I did, and even now, it is fun being involved. There are too many people who are stuck in places they’d rather not be. That could never be me. It’s been fun to be on the whole journey,” Harry says. “On the whole train.”

Harry retires this month after an incredible 55 years at Kässbohrer All Terrain Vehicles, Inc. He is looking forward to spending time with his wife, children, and grandchildren in the beautiful state of Maine.